Welcome to Paradoxa

Paradoxa is a peer-reviewed, scholarly periodical that publishes articles on genre literature: science fiction, horror, mysteries, children’s literature, romance, comic studies, the fantastic, the occult, westerns, oral literature, and more. Paradoxa invites submissions on all aspects of genre literature which make a significant and original contribution to the study of those genres. Find Submission Guidelines here. Paradoxa has been independently published since 1995.

Please note that Books and Individual Articles from Paradoxa are now available on this website to purchase and download on our Volumes page. For more information on rates and ordering options, including an Unlimited Access Pass (accessed via IP authentication or by Username-and-Password), please visit the Rates page. All income from the sale of books and articles supports the continued publication of Paradoxa. We will continue to add new material so come back to visit. Please Contact us if you are interested in specific back issues that are not yet available on-line.

Current Issue:

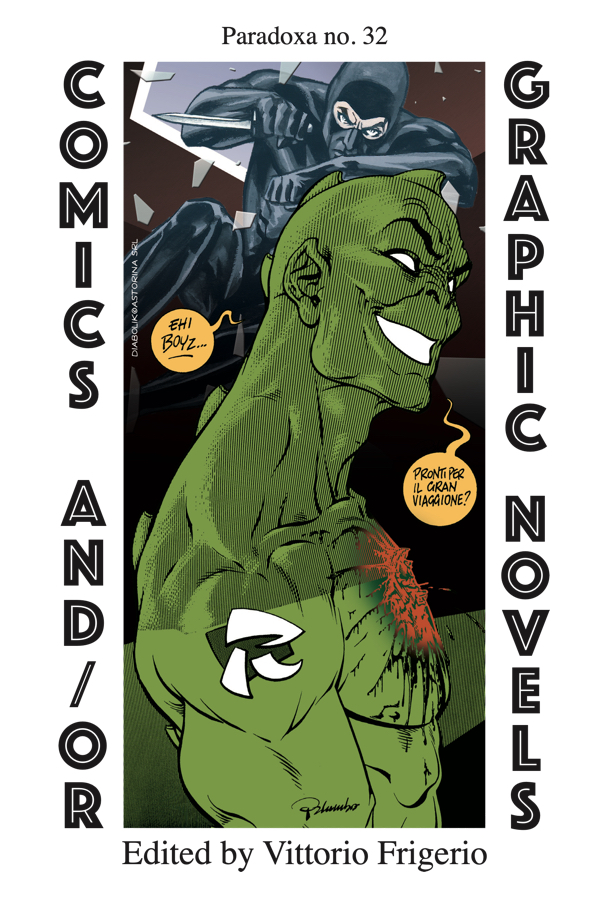

Paradoxa, Volume 32, Comics and/or Graphic Novels (Now available for download; print copies available by early 2022)

Editor: Vittorio Frigerio (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada)

Next Issue, Volume 33:

Moroccan Narratives: Postcolonial Prisms

Morocco is a nation animated by an extraordinary array of narratives – written, spoken, chanted, sung, and filmed in an intricate mosaic of languages and their variations. The ancient art of storytelling lives on and is articulated in many languages, Tamazight (the language of the Amazigh people), in Arabic (both Fusha, or standard Arabic), and in Darija, (the vernacular Arabic spoken by most Moroccans), as well as in French, Spanish and English.

The narratives that emerge from this swirl of languages with its ebbs and flows, its problematics of translation and identity and agency, are the focus of this special issue of Paradoxa. We encourage submissions of essays from a variety of perspectives and disciplines that address one or more of the following narrative spaces in the rich, complex culture of postcolonial Morocco:

Victor Reinking – vicr@seattleu.edu, Fatima Matousse – f.matousse@gmail.com

Issue in Preparation, Volume 34

Salinger After Salinger

Ten years ago, David Shields and Shane Salerno did J.D. Salinger’s readership a major, even revivifying favor by publishing the doorstop-sized critical biography, Salinger (Simon & Schuster, 2013). Weighing in at a robust 699 pages, the book immediately caused a sensation by its many revelations and its virtually psychedelic connectivity. A documentary film version, directed by Salerno, also helped to convey the authors’ findings further into the mainstream.

Most tantalizingly, in the book’s final chapter (“Secrets”), we learn of the existence of a “stack of manuscripts” kept in a locked safe in Salinger’s “bunker,” a building he installed separate from the main house on his property outside Cornish, New Hampshire, where he labored at the keyboard virtually every day from 1965 to 2010.

Shields and Salerno state in their conclusion: “Salinger’s chronicles of two extraordinary families, the Glasses and the Caulfields—written from 1941 to 2008, when he conveyed his body of work to the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust—will be the masterworks for which he is forever known.” Their final sentence, however, rings somewhat ominously today: “These works will begin to be published in irregular installments starting between 2015 and 2020.” Unhappily, those speculative dates have now expired with nothing having been published thus far.

Among the manuscripts marked by Salinger as “ready for publication” after his death, Shields and Salerno also list a book-length “manual” for Vedantic religion, told in fables “woven into the text.” The biography details Salinger’s abiding interest, from the early 1950s until 2010, in Advaita Vedanta, a philosophical school of Hinduism based on three antique source-texts: the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita. This “one constant” in Salinger’s postwar life, according to Shields and Salerno, “transformed him from a writer of fiction into a disseminator of mysticism, destroying his work and, over time, causing him to turn silent in order to fulfill the final stages of his religious doctrine.”

Trauma may be the most prominent cause behind such a radical shift in personality, and at least two major—i.e., near-psychosis-inducing traumas–afflicted the author’s life. The first derives from his WW II experiences, culminating in his entry, in April 1945, into Kaufering IV concentration camp, a subcamp of Dachau. The second major trauma, it seems, results from the critical reception accorded to Salinger’s last published work, “Hapworth 16,1924,” published in The New Yorker in 1965 and mysteriously never reprinted, except clandestinely.

Is there a way to understand the teachings of Vedanta as a living source of sense-making, not as the reason for the “destruction,” of Salinger’s post-1965 writing? Is there a way to connect these two biographical aspects of the author’s life without rushing to judgment on one over the other? Aren’t there teachings from the sacred literature of Hinduism that might actually illuminate the eschatology for storytelling, far more substantial that merely critical, sadly “literary” opprobrium?

In 2001, Janet Malcolm published a landmark response to such questions, in an essay titled “Salinger’s Cigarettes,” which she later included in Forty-One False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2013, 111-127). Malcolm’s essay samples contemporary (to 1965) critical responses to works Salinger published before 1965: “When Franny’ and ‘Zooey appeared in book form, a flood of pent-up resentment was released,” she writes. Literary frumps like Maxwell Geismar had condemned “Zooey” as “an interminable, an appallingly bad story,” while George Steiner called it “a piece of shapeless self-indulgence.”

Malcolm then moves to the final story Salinger published, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” exposing the splenetic venom found in reviews by many of the literary elite in those days: Alfred Kazin, Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, John Updike, and many others. Their unvarnished hatred for the story “was more like a public birching,” she wrote, “than an ordinary occasion of failure to please.”

The editors of Paradoxa invite readers of Salinger’s oeuvre to address these and related topics in essays incorporating their own personal, lifetime reading in direct relation to, and confrontation with, their own physical and spiritual lives. How, in your experience in life and as a reader of Salinger’s work, does/did the effect of Salinger’s writing change you? He once called The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna “the religious book of the [twentieth] century.” Is there a “poetics of conversion” that might likewise describe your experience?

But beware: This terrain is notoriously tough trekking, precisely because there’s inherent risk in such powerful, personal transformations. Not one, not two, but three assassins of public figures were found either with a copy of Catcher in their pocket at the scene of the crime (Mark David Chapman, killer of John Lennon), or cited by would-be assassin (John Hinkley) as the explanation for his motive in shooting Ronald Reagan and his press secretary or, as in the case of a star-struck fan (the aptly-named Robert Bardo) carrying a copy with him to kill actress Rebecca Shaeffer in 1989. Salinger’s writing has served readers as both a manual for assassins and an inspiration toward transcendence.

We ask that authors interested in contributing to this issue submit a one-page (maximum 350 words) abstract of their essay to one of the editor by November 1, 2023. This collection of essays will be edited by James Winchell, <wincheja@whitman.edu>

If/when the editor approves your abstract, submissions are normally between 15 and 30 pages. Submissions should be double-spaced and sent as a Word document. Please note that all manuscripts will be subject to close editing and suggestions for revisions. The deadline for receipt of essays is January 30, 2024. Authors will receive a proof of their work which they are expected to read and correct, and return as soon as possible. We plan to publish the issue late in 2024 or early 2025.

Announcement of the Winner of the Martin Schüwer Publication Award 2022

“Dr Felipe Goméz’ most recent research project is dedicated to the manifestations of resilience and perseverance in Latin-American comics that feature apocalyptic settings. [He emphasizes an] analysis of the aspects of race and gender which are reflected in the community and its protagonists’ survival strategies. His article “Would it be possible? Apocalypse and Resistance in Latin American Graphic Novel” (Paradoxa no. 32, “Comics and/or Graphic Novels” 2021), is an important addition to contemporary research on apocalypses and post-apocalypses. His focus, however, is on a subject that has been marginalized and underrepresented in more than one way: First, Latin-American comics, which are front and center here, are much less represented in international research than comic traditions of the northern hemisphere. Second, the research on the genre of science fiction, to which (post)apocalyptic scenarios belong, has focused on Eurocentric perspectives for a very long time. Only recently has research on science fiction in the southern hemisphere gained momentum. In this context, hegemonial narratives are exposed, and marginalized perspectives revealed. Dr Felipe Goméz’ award-winning article makes a crucial contribution to the broadening of research perspectives.”

American histories of comics have traditionally highlighted what they deem the indisputable U.S. birthplace of this mass-culture phenomenon, pointing to Richard F. Outcault’s Yellow Kid (1895) as the first comic ever produced. Alternately, the European view tends to favor the creation of this ever-popular medium by Swiss author Rodolphe Töppfer, with his Les Amours de monsieur Vieux Bois (1827 – first published in 1837) and highlights the importance of early works such as German author Wilhelm Bush’s Max und Moritz (1865).

A similar, apparently irreducible dichotomy has appeared concerning the origin of the “graphic novel.” American critics consider Will Eisner’s A Contract with God (1978) as the first graphic novel ever produced, while European historians point to Hugo Pratt’s La Ballata del mare salato (1967 – although its influence is said to be felt primarily after its translation into French in 1975). And it is not unusual to see credit for the origin of the graphic novel given to the Argentinian El Eternauta, by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López (1957).

Apart from matters of national pride and predominance, these divergent views are also due to unresolved questions regarding the meaning of the terms involved. Töppfer’s books would not qualify as a comic if one were to consider the genre as primarily defined by the use of the speech balloon. But then neither would such seminal works as Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon or Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. In the Franco-Belgian domain, debates have also excluded such historically significant works as Joseph Pinchon’s Bécassine or Louis Forton’s Les Pieds nickelés. In the Italian tradition, practically all pre-Second World War productions, such as Sergio Tofano’s Signor Bonaventura or Antonio Rubino’s Quadratino would automatically be excluded.

The final definition of “graphic novel” remains open to debate, as any customer of a major North American booksellers’ chain knows full well. Major commercial publishers recycle “classic” comic book fare under a new label and present it beside recent, more “literary” productions issued by niche or alternative publishers. Indeed, we can easily go from all-encompassing definitions such as offered by Stephen Weiner…

“Graphic novels, as we shall define them for this project, are book-length comic books that are meant to be read as one story. This broad term includes collections of stories in genres such as mystery, superhero, or supernatural, that are meant to be apart from their corresponding ongoing comic book storyline; heart-rending works such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus; and non-fiction pieces such as Joe Sacco’s journalistic work, Palestine.” (Stephen Weiner, Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel. Introduction by Will Eisner. NBM Publishing, 2012.)

… to much more restrictive and specific ones, like that proposed by Thierry Groensteen…

“[T]he comics medium has matured, […]. Its standing has greatly improved, to the extent that it is now regarded as a form of literature in its own right. It has diversified by moving into new areas (history, personal life, science, philosophy, sometimes poetry) and by taking on new forms (diary, reportage, essay).” (Thierry Groensteen. The Expanding Art of Comics. Ten Modern Masterpieces. Translated by Ann Miller. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2017, p. 3.)

Such appraisals also seem to vary according to the national origin of the critic, with North American criticism generally more willing to include mass cultural products within the field of the graphic novel, while European critics highlight notions of “maturity” and generic evolution that reserve the label for productions outside of, or in the margins of the commercial mainstream. Comics, bandes dessinées, fumetti, tebeos, manga—as they are known with important variations in different cultural contexts—and their critical reception, thus appear to differ significantly depending on their national histories and cultural preferences, and are only superficially identical.

On the other hand, comic book characters, their authors, and their publications have crossed national and linguistic boundaries to an extent rarely seen in the world of literary fiction. Any account of the Franco-Belgian “bande dessinée” would be incomplete without acknowledging the impact of Golden Age American comics, either as aesthetic models (George McManus’s influence on Hergé, Caniff’s influence on Jijé and other artists of the realistic school of drawing), or as competitors whose symbolic dominance led to the development of an autochthonous industry. American underground comics and authors of Mad magazine inspired the creators of the French Pilote and encouraged the transformation of the medium so that it appealed to the tastes of an older audience. In return, Franco-Belgian “ligne claire” informed some notable contemporary North American creators (Jeff Smith, Chris Ware…) and even influenced the international art world (Dutch illustrator Joost Swarte).

A constant whirlwind of reciprocal influences has marked the evolution of the comic genre across North America and the major European markets, as well as important markets in Latin America, most notably Argentina. Hugo Pratt, Alberto Ongaro, and Mauro Faustinelli contributed importantly to the development of the genre in that country, while European translations of Argentinian authors such as Alberto Breccia, have helped generate cultural recognition for the new genre of the graphic novel. Not all experiments were equally successful. Moebius (pseudonym of French author Jean Giraud), invited by Stan Lee to draw the famous Silver Surfer, did not meet with unconditional approval in the U.S. Periodic attempts at translating celebrated series such as Tintin and Astérix for an English-speaking public have not been able to duplicate the success of the characters in their respective native countries. The iconic Italian western Tex Willer is a major hit in Brazil, but only one story has appeared in North America, and then only because it was drawn by well-known American artist Joe Kubert.

In recent decades, the increasing critical recognition of comics as a legitimate artistic and literary genre has spawned the creation of several significant international events, such as the Angoulême International Comics Festival (France) and the Lucca Comics and Games convention (Italy), helping to further break down barriers and to bring national traditions into ever closer contact, while at the same time favoring the representation of comics as specific national products deserving of state sponsorship and protection granted through agencies such as the “Centre belge de la bande dessinée” in Belgium or the “Cité international de la bande dessinée et de l’image” in France.

What can a transnational analysis of the development of comics and graphic novels teach us about the nature of the genre? Do the exchanges and circulations (of authors, characters, styles, subjects, publishing formats…) between national traditions allow for a rewriting of the evolution of graphic narratives, outside of nation-based or linguistic models? What do these migrations tell us about any immutable or invariable properties potentially common to graphic narratives, independently of their chronological and geographical positioning, their intended audiences or their degree of cultural recognition? How and to what extent can the historiography of comics and graphic novels benefit from adopting a global approach to the subject?